Whilst many women are celebrated and respected in society, there are still a large majority of women who live in fear and are not given the freedom that they deserve. Gender inequality still exist and crime against women are still a constant battle; whether it may be sexual discrimination or violence, force marriages or female foeticide.

According to a report published by the Forced Marriage Unit, the majority of forced marriage cases dealt with in the past originate from Pakistan (42.7%) and India (10.9%) and the top two cities where it is found in the UK is London (24.9%) and West Midlands (13.6%).

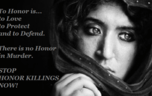

Figures from the Metropolitan Police show that there are approximately 12 cases of honour killings each year and thousands of cases of honour-based violence. The actual figure is unknown but is likely to be much higher due to many victims not coming forward for fear of ostracizing their entire family and being disowned.

These heinous crimes may not seem like a relatable concept to some, however, it is the harsh reality of many living in the UK; one prime example being Neda. Neda is one of over 3000 victims who suffer honour-based abuse each year and are faced with a glass ceiling that is instigated by culture and religion.

As a teenager, all Neda ever wanted to do was study. Sadly for her, her family had other plans. Aged 11, she arrived in the UK with her family as a refugee but lost her mother to Leukaemia shortly after. Everything changed when her father remarried and the abuse started. “My stepmother controlled what books I read, everything was about learning to cook and doing housework. It was so humiliating to have those limitations simply because we were girls.”

When she discovered that her parents were making plans to force her 16-year-old sister to marry a man in his forties, Neda called the police. However, rather than offering support, the girls were dismissed with the words, ‘we can’t do anything, this is your culture, isn’t it?’

Neda was forced to take action that day realising that there was nobody to help. She ran away with her sisters, and with almost no support, raised them both on her own. During this time, she says, she started losing faith in God.

“It was after my mum passed away,” she says. “Perhaps it was my anger at my mum’s death but also by looking at the way women were treated, not in my religion, which was Islam, but in Iran in particular, the way men used religion as a way of repressing women. I started seeing that more and more and couldn’t accept it as a religion anymore.”

What is honour-based violence and why does it occur? Polly Harrar, founder of Sharan Project, a charity that supports vulnerable women who have left home forcefully or voluntarily, says it sadly begins in the home with your own family. Family members, usually men but sometimes women, come together to deem someone’s behaviour as unacceptable and “seek their own justice by deciding or self-policing their own punishment on that person.” There is not one type of honour-based violence, she says, but it varies depending on a “case-by-case basis”.

Honour-based violence typically takes place when someone defies parental control, becomes too ‘westernised’, has sexual relationships before marriage or uses drugs or alcohol. Forced marriages are also a large instigator for this abuse. Because there is an invisible cultural barrier, the abuse is often overlooked and can lead to thousands of women slipping under the radar.

Human rights activist, Mandy Sanghera, who has been supporting women and vulnerable adults for the last 24 years, has called for more awareness. “We need to tell the perpetrators that some of these values they hold dear in their community will not be tolerated. People are hiding under the umbrella of ‘honour’ to repress women. But there is nothing honourable about killing or abusing someone in the name of honour.”

This type of violence can typically include physical or emotional abuse, forced marriages or female genital mutilation (FGM) and can occur in any community. Most of the known cases, however, have taken place in the South Asian and Middle Eastern communities, which have strong influencing cultures and a shared belief system that often prioritises the view of society over the rights of a human being.

Within these cultures, the idea of honour comes from the perception that a woman is not an individual, but part of a united identity, identified and bound by her family surname. Women are often seen as possessions of the male members of the family and therefore, anything they do impacts the family. The wider community then fail to acknowledge the barrier these women face, because the perpetrators’ use the argument that it is ‘part of our culture’ or ‘part of our religion.

As for Neda, she is now an atheist. “I’ve never made any decisions to reject religion but I don’t practice it and no longer believe it. Deep down I know its not religion but I don’t want it. I know what I’ve been told all my life and religion has certainly been used to oppress women, if it’s not itself oppressive”.